Two commercial buildings, a factory and an aerospace research facility, both consumed 40,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) of energy in January 2017. However, their energy consumption patterns were very different. The factory maintained a uniform energy consumption of 1,333 kWh per day, and for no given period did their power draw exceed 56 kilowatts (kWs). Conversely, all of the aerospace research facility’s power consumption came in brief spurts: once a week it turned on its wind tunnels for 15 minutes. During each 15-minute interval that the wind tunnel was on, it consumed 10,000 kW. Which of these two buildings will have the higher utility bill? Can solar help both institutions save money? (Scroll to the bottom for answers.)

To answer these questions, one must understand how commercial entities are billed for their electricity usage. Most commercial customers have utility bills that are divided into two major categories:

- Energy consumption: the amount of energy (kWh) consumed, multiplied by the relevant price of energy ($/kWh) during the billing period.

- Demand: the maximum amount of power (kW) drawn for any given time interval (typically 15 minutes) during the billing period, multiplied by the relevant demand charge ($/kW).

As a solar professional, if you want to accurately communicate the value that a solar installation will provide to a commercial customer, it is critical to understand demand charges and how they affect your client’s utility bill.

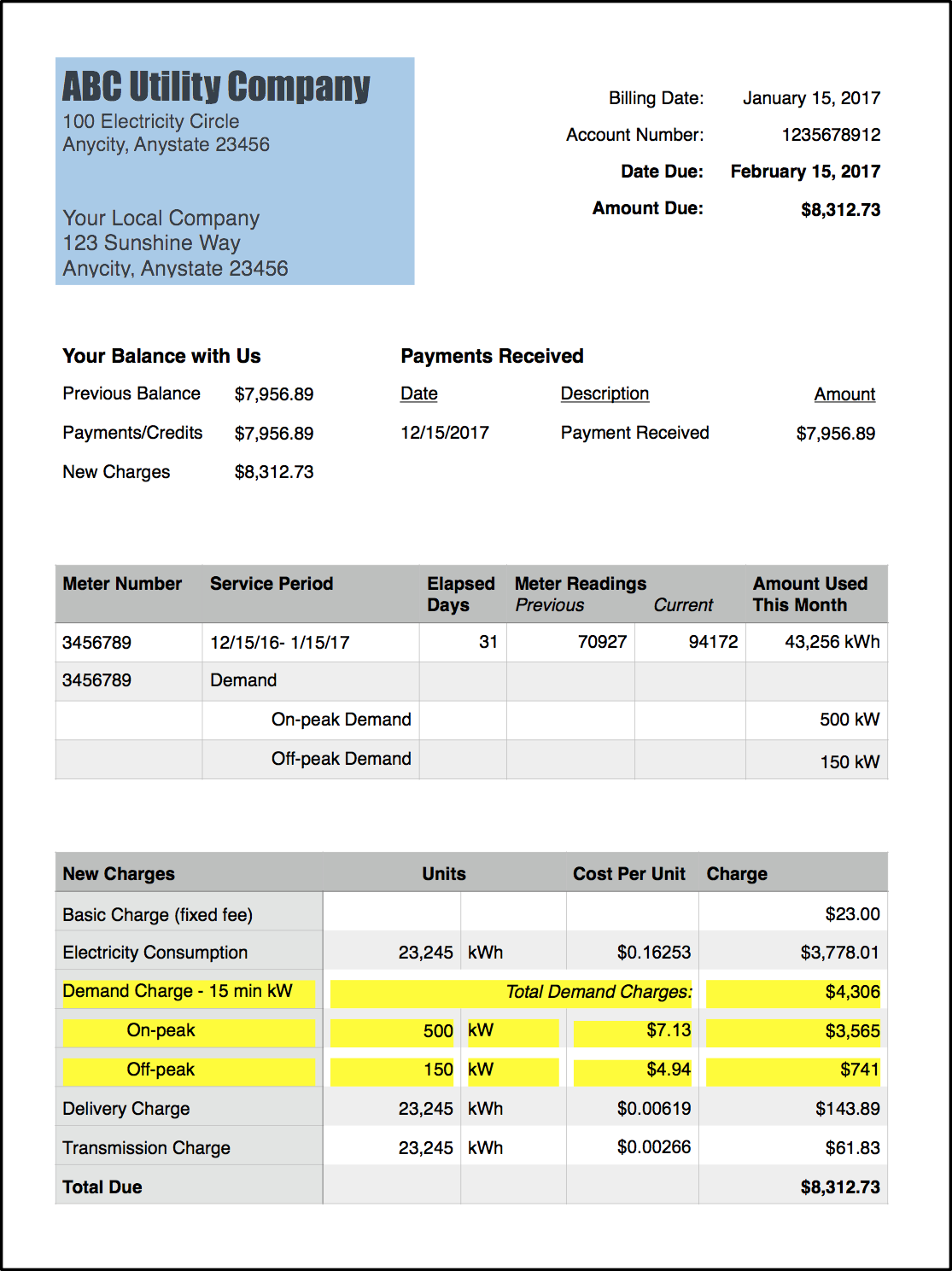

A sample utility bill depicting demand charges (highlighted in yellow).

A sample utility bill depicting demand charges (highlighted in yellow).

How Do Demand Charges Work?

Demand (measured in kW) is a measure of how much power a customer uses at a given time. Utilities apply demand charges based on the maximum amount of power that a customer used in any interval (typically 15 minutes) during the billing cycle. Demand charges usually apply to commercial and industrial customers, who tend to have higher peak loads (i.e. peak power demand) than residential customers. Most utility rates specify the maximum power demand a customer is allowed to have: exceeding the maximum power demand for consecutive months can result in being moved to a different rate with higher demand charges.

Utilities apply demand charges based on the maximum amount of power that a customer used in any interval (typically 15 minutes) during the billing cycle.

To determine the demand charge for a given month, the maximum power demand is multiplied by the demand charge rate of the prevailing utility rate. While the exact billing approach varies by utility, some rate structures include multiple types of demand charges, with higher charges during hours of peak demand, and lower charges during “partial-peak” or “off-peak” hours (Time of Use Rates). For customers whose utility rates include them, demand charges can contribute significantly to monthly electric bills.

Let us consider an example of how demand charges are calculated. The basic formula to calculate demand is:

X kW of demand * Y $/kW = $ Monthly Demand Charge

If the utility rate sets demand charges at $9.91 per kW, and the customer has a peak demand of 500kW for the month (reflecting the 15-minute interval in which they consumed power at their highest rate), the demand charge would be calculated as:

500 kW * $9.91 = $4,955

More complicated rate structures may include different demand rates during different times (for instance peak and off-peak hours). For example, a utility might define on-peak hours as 6 a.m. to 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. from November through March, and from noon to 9 p.m. from April through October. The peak rate for demand is $7.13 per kW and the off-peak demand rate is $4.94 per kW. In January, the customer’s maximum demand during peak hours was 500kW. Their maximum demand during off-peak hours was 150kW.

Their demand charges would be calculated as:

On-peak Demand: 500kW * $7.13 = $3,565

Off-peak Demand: 150kW * $4.94 = $741

Total Demand Charges for January = $4,306

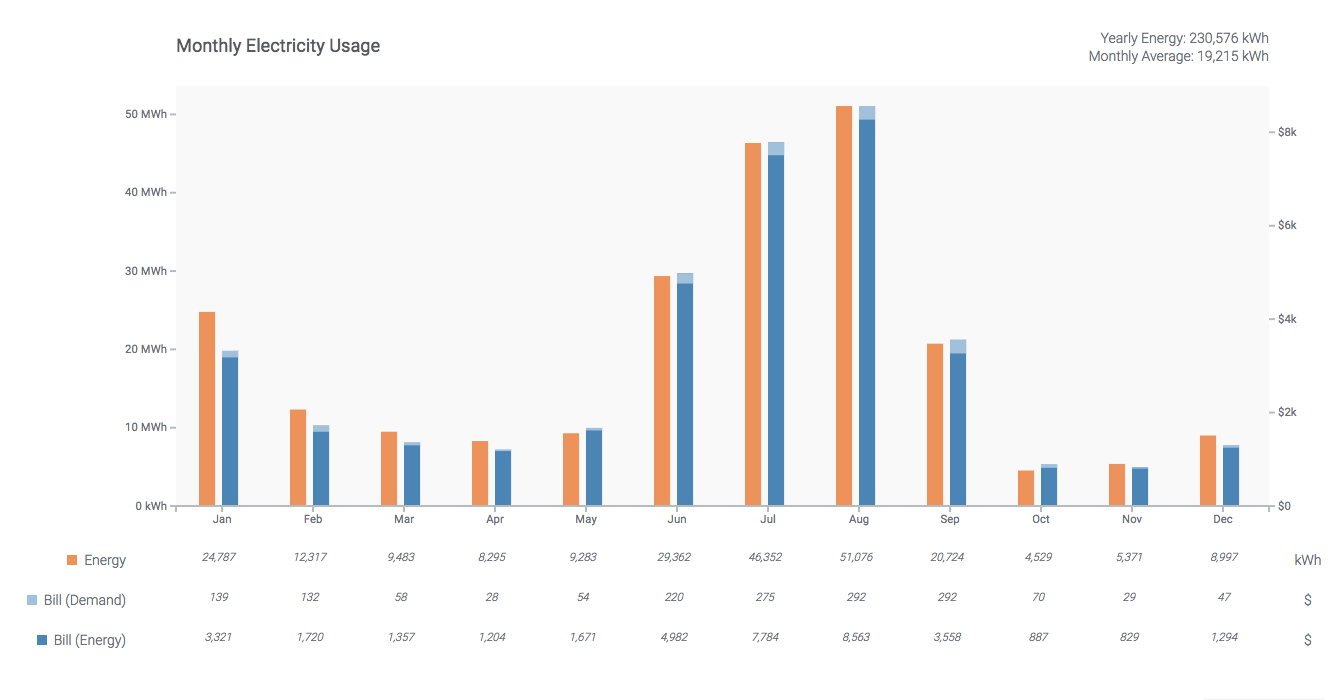

An example of a (different) commercial customer’s monthly energy consumption (orange) and bills (blue) based on sample Green Button Data imported into Aurora; the portion of the bill comprised of demand charges is shown in light blue.

An example of a (different) commercial customer’s monthly energy consumption (orange) and bills (blue) based on sample Green Button Data imported into Aurora; the portion of the bill comprised of demand charges is shown in light blue.

How Does Solar Affect Demand Charges?

The impact of solar is relatively straightforward when it comes to consumption charges: by producing electricity from a solar installation, a commercial customer can reduce the amount of energy they must buy from the utility and thereby reduce utility bills.

Unfortunately, when it comes to demand charges, solar does not provide consistent cost savings. Because solar energy production varies based on weather conditions and time of day, periods of high solar power will not always coincide with the times when a building has its highest power demand. This means that solar customers cannot count on their solar systems to reduce demand charges. A chance rainstorm at a time when the facility happens to use energy at its highest rate during the month would result in a demand charge as high as it would have been before installing solar.

Despite this, it is important to understand this element of the customer’s bill in order to understand what portion of the customer’s costs solar can offset. We’ll explore the financial impact of demand charges for commercial solar customers in greater depth in a future blog post.

Why Do Utilities Apply Demand Charges?

Demand charges exist to incentivize customers to spread their energy usage over time. This is because utilities must maintain enough generation and distribution capacity to meet the needs of all customers during the points in time when the most energy is drawn from the grid (such as a hot day when most customers are using air conditioning). This means that a large amount of expensive equipment, such as power plants, must be kept on standby for these rare peak demand periods. Through demand charges, customers that draw a lot of power over short periods of time contribute more to the costs of building and maintaining the necessary infrastructure needed for peak times.

Demand charges were first introduced in the early 1900s by Samuel Insull, a colleague of Thomas Edison and an influential figure in the expansion of electricity access in the US. They have remained a common approach for commercial electricity billing since then.

Discussing a proposal to apply demand charges to residential customers in Illinois in 2015, in comments to Midwest Energy News , Fidel Marquez, a senior vice president with ComEd, summarized the utility rationale for demand charges as a way to “correct inequities that can result in low-usage customers subsidizing high-usage customers.” He also noted that “the costs of delivering electricity are driven by the demand that customers place on the system whenever they need it, and ComEd builds and maintains its delivery system — poles, wires and transformers — to handle everyone’s maximum demand for power.”

However, there are diverse perspectives on the efficacy of demand charges as a means to reduce peak demand on the grid and some pro-solar groups argue that demand charges are harmful to the value proposition for solar.

Irrespective of the reasons for demand charges and how effective they are, they are not going away so it is important to have a strong grasp of how they work. Understanding demand charges allows solar installers and customers to accurately assess what portion of a monthly bill can be offset with solar and provides a starting point for exploring additional options for reducing peak demand.

Key Takeaways

- Demand charges are fees applied to the electric bills of commercial and industrial customers based on the highest amount of power drawn during any (typically 15-minute) interval during the billing period.

- Demand charges can comprise a significant proportion of commercial customers’ bills.

- In the example from the introduction, we can expect that the aerospace research facility will have a higher monthly bill than the factory, although both have the same monthly energy consumption. The aerospace research facility will have significantly higher demand charges because its peak demand is much higher.

- Solar can save both institutions money by reducing their energy consumption, but it will not reduce as much of the aerospace research facility’s bill because solar cannot consistently reduce demand charges.